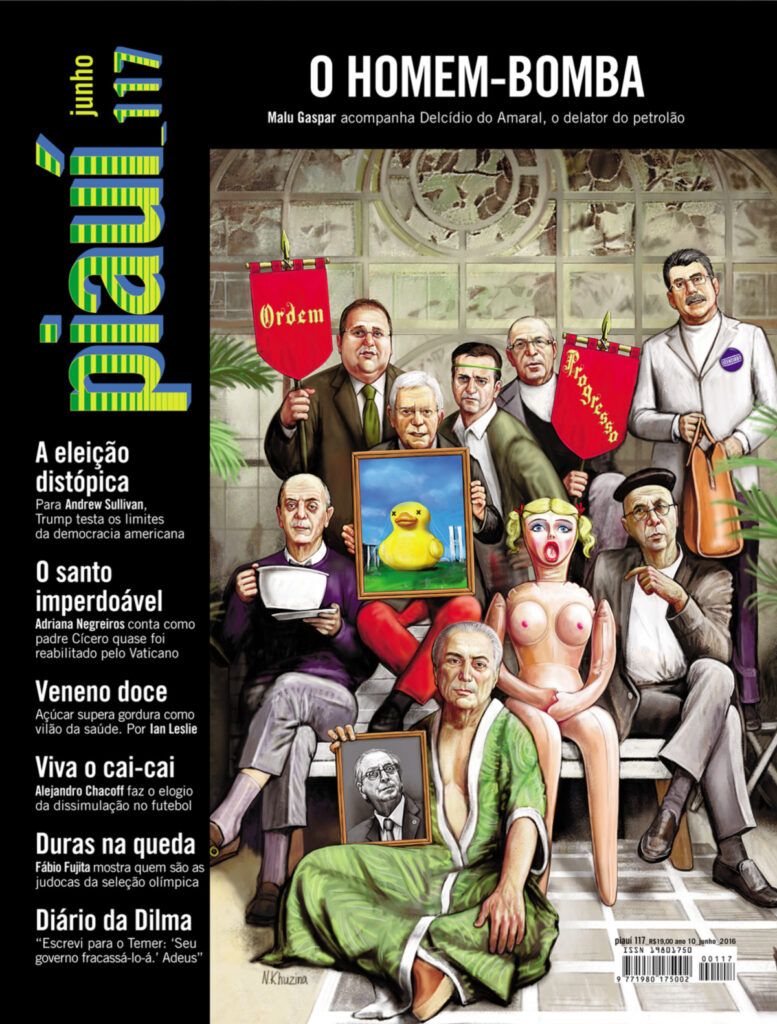

1 Nadia Khuzina, Illustration from Piauí magazine, 2016, a parody of the cover of the album Tropicalia ou Panis et Circencis, created by artist Rubens Gerchman in 1968, featuring figures from the New Right, Piauí magazine, last accessed on 17 December 2025.

Kathrin Rottmann (KR), Friederike Sigler (FS): Following Jair Messias Bolsonaro’s election as President of Brazil at the end of 2018 and his inauguration on 1 January 2019, a series of cultural policy changes were implemented. Although cultural policy was not a central issue during the election campaign, it has since become a key concern for the New Right. For instance, Bolsonaro frequently invoked the concept of ‘culture wars’ against ‘Marxist culture’ in interviews and implemented substantial structural and personnel changes within the art scene, which was renowned for its liberal cultural policy and cultural diversity. What has changed under Bolsonaro’s government? In what ways has the new right-wing cultural policy been manifested in Brazil – in institutions, administration, staff?

Luiza Proença (LP): It is important to contextualize at least two aspects to answer this question. First, we must differentiate Bolsonaro from ‘Bolsonarismo’, the latter being the articulation of diverse groups that gave a new expression to the right in Brazil and act relatively independently of Bolsonaro, who was elected president by them in October 2018. I will try to address both, but I will focus mainly on Bolsonarismo. Secondly, I consider it crucial to take into account the affective positions we take in politics, so I would like to situate the point of view from which I followed the growth of the conservatism movement and some of the experiences that guide me in this interview.

I was born in 1985, just when Brazil’s democratic transition was beginning after 21 years of military dictatorship. By the early 1980s, many artists and intellectuals had returned from exile, and the Workers’ Party (PT) was founded from the confluence of heterogeneous groups. Among those who returned was the psychoanalyst Suely Rolnik who, alongside philosopher Félix Guattari, traced the reorganization of the socio-movements and the political experiments during that time.[1] I mention Suely because it was through her work in subjectivity studies that I was able to think about the transformation of the political and cultural cartography as I knew it, which you described as “liberal” and “diverse.”

The cartography I am referring to was developed during the 1990s and 2000s. In 1991, a law called “Lei Rouanet” was created, allowing companies to direct part of their taxes to cultural projects pre-approved by the State. This financial mechanism has many contradictions. It made the artistic production more susceptible to the logic of the market, as companies tend to support initiatives aligned with their interests and image. It also contributed to the consolidation of an artistic class, especially in the Southeast of the country, where private capital is concentrated – and this helps explain subsequent political tensions. For instance, the company Brasil Connects organized the so-called “mega-shows,” breaking audience records, such as Brasil +500 (2000), an exhibition celebrating the “re-discovery” of the country since the first colonial invasion. The company was created by the banker and ex-president of the São Paulo Biennial, Edemar Cid Ferreira, who was later convicted of crimes such as criminal conspiracy and money laundering. This reveals how the tax incentive policy could be used by large private players for projects with enormous visibility, while exposing the cultural sector’s vulnerability to the use of art for neoliberal interests and corruption schemes. The U.S. artist Andrea Fraser has documented the spirit of that period very well in her proposal for the 24th São Paulo biennial (1998), the so-called ‘anthropophagy biennial’, another audience success and probably the most celebrated contemporary art event of South America. In a series of video interviews in partnership with state television, the artist exposed the contradictions of the biennial’s corporate sponsorship and the quest for internationalization of the Brazilian art scene.

I began my studies in visual arts in 2003, the year Lula historically assumed office as president, after three previous attempts in which he held a more radical position. The singer-songwriter Gilberto Gil took over the Ministry of Culture, bringing the spirit of ‘Tropicália’, an aesthetic movement that challenged authoritarianism during the years of dictatorship. His ministry created networks that encouraged autonomy in artistic and cultural production, especially with the so-called ‘Pontos de Cultura’ distributed throughout the country. From my perspective, in the first decade of the 2000s there was more mobilization, collectivity and experimentation, and less dependence on private capital from Southeast Brazilian institutions.

In the early 2010s, signs that things were not going so well began to appear. Dilma Rousseff was in her first term, succeeding Lula, and I was working on my first curatorial projects. There was widespread economic optimism, fueled by the resumption on the Belo Monte hydro-electric dam in indigenous territories of the Amazon rainforest, the discovery and exploration of pre-salt oil reserves on the coast of the country, expectations for the World Cup (2014) and the Olympic Games (2016) in Brazil.[2]As part of this optimism, the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo promoted art as “a barometer of the economy” and “an engine of development”.[3] In fact, the art market was overheated at that time, and as a young curator, surrounded by emerging artists, I found myself getting involved with the Brazilian cultural elite, despite some malaise.

I’m introducing this context in a somewhat lengthy manner, even with limited details, to risk stating that the new cultural policy of the right-wing was already manifesting itself at that time, given that a significant part of the elite around contemporary art were (or still are?) Bolsonaro supporters.[4] I’m not saying that we were witnessing the emergence of “right-wing works of art”, but that a field of art permeated by neoliberal and conservative elements was growing. Marina Vishmidt proposes that fascism should be understood as an infrastructural phenomenon, and the art world, regardless of the content of the works, is structurally right-wing.[5] From a micropolitical perspective, Suely Rolnik demonstrates how capitalist-colonial subjectivity converts creation, the essence of life, into “creativity”, transforming art into a coveted field for the accumulation of capital. Such abuse forces art practitioners to operate according to the logic of recognition, individualism, and competition, generating resentment, anguish, and other sad and dangerous affects. In addition, Rolnik asserts that since the left gained power in Latin America, financial capitalism has formed an alliance with conservative forces so that the latter could do the dirty work of clearing the ground of barriers to its free circulation. This provisional alliance has resulted in the new far-right in Brazil, articulating what she calls a “new kind of coup d’état”.[6] We might add that this new strategy is also the symptom of a class that is increasingly aware of the fact that, with the climate crisis, there is not and will not be enough world for everyone, as has been pointed out by the writings of Deborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro.[7]

These aspects within the art field became even more evident to me when I joined the curatorial team of the 31st São Paulo biennial, whose exhibition and program took as a starting point the driving force behind the protests that were taking place on an international scale, such as the Arab Spring (2010) and Occupy (2011), and more specifically in Brazil since June 2013. June 2013 is considered the most significant mass political event in Brazil since the struggles to end the military dictatorship in the 1980s; it started as a protest over public transportation fare increases, but it ended up serving as a platform for the expression of a general discontent with the government. The works of the 31st Biennial experimented what artists, activists, communities, and various agents could develop from the matters of concern that came up during gatherings and open meetings – they included old wounds such as state terrorism, abortion, sexuality, the right to the city, and indigenous lands. But divergences in political perspective between the curators (a collective of seven people of different nationalities trying to work horizontally) and the foundation’s board of directors (composed mainly of businessmen) soon came to light. The trigger came on the eve of the opening of the event, in September 2014, around a disagreement over maintaining the State of Israel’s sponsorship. Journalist Fabio Cypriano writes how this case revealed the foundation’s lack of sensitivity in failing to understand that infrastructure issues, such as funding, may have a significant impact on the artistic proposals. This disparity lies in these agents’ ambition to occupy the role of “art collectors,” a title that allows them to circulate with prestige in museum’s galleries and boards in the Global North, especially in the United States. As a result, it presupposes a disinterest in culture as crucial to life and a space for social change.[8]

Another episode – this one emblematic of the “culture wars” mobilized by the right-wing and marked by moral repudiation of contemporary art exhibitions – occurred at the same 31st biennial, when this was already opened to the public. Instituto Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira (IPCO) – linked to the organization ‘Tradition, Family, and Property’ – carried out several demonstrations against some artistic works, such as the work Espacio para abortar (Space for abortion) by Mujeres Creando collective. The work was built from intimate testimonies from women who underwent abortions, which are still illegal in most South American countries. The fuss caused by IPCO reached the São Paulo State Department of Education, which in turn led the Biennial’s superintendence to take censorship measures, based on unclear criteria, including the decision to prevent educators from incorporating certain works into their visit itineraries for school students.

We would find several other examples that confirm the presence of culture wars in Brazil looking back at the 2010s. Diogo de Moraes Silva and Pablo Ortellado have produced relevant work on some of these cases, highlighting that the phenomenon gained greater prominence in the second half of 2017, when a series of conservative protests against artistic institutions spread across the country.[9] The closure of the exhibition Queermuseu: Cartografias da diferença na arte brasileira (Queermuseum. Cartographies of Difference in Brazilian Art), at Santander Cultural in Porto Alegre, is the most notable example.

Through these examples, I want to emphasize that the “easy” answer to your question would be to say that the cultural policy of the new right-wing in Brazil has manifested in attacks and harsh persecution of everything that promoted left-wing thinking, such as Paulo Freire (one of the most widely read authors in the world), social movements (such as feminism and LGBTQIA+), and artistic practices surrounding issues of sexuality, gender, and religion (in the eyes of the far right, “profane art” financed with public resources). Similarly, one could say that what changes when Bolsonaro took power is the formalization of this policy of destruction of everything that had been built since the end of the dictatorship, with the aim of “shooting down” the entire center-left imaginary. In fact, he dissolved the Ministry of Culture; made significant cuts to agencies such as the audiovisual agency (Ancine); restricted and modified the Lei Rouanet; and undermined indigenous and quilombola cultural policies. It is no coincidence that Bolsonaro’s main ally was Paulo Guedes, a former student of the Chicago School, the institution that created the strategy that Naomi Klein called the “shock doctrine,” that is, “wiping the slate clean” in order to impose reforms.[10] Appointed “super minister of the economy,” Guedes lent credibility to Bolsonaro’s candidacy in the financial market and signaled a break with the interventionism of previous governments, amid a scenario of profound institutional discredit.

It is unlikely that Bolsonaro, having only two bills approved in 27 years as a congressman, had any other consistent proposals for the cultural sector. In an attempt to justify his “misgovernment,” he even claimed on several occasions that he was unable to work during the pandemic because the Supreme Court had interfered with his administration’s decision-making power in relation to COVID-19.

We can also speculate on what kind of art could suit the various interests and classes that converged into the Bolsonarismo. Rodrigo Nunes argues that a broader understanding of Bolsonarismo requires analyzing aspects such as: the discursive matrices that converged in its formation (he lists militarism, anti-intellectualism, entrepreneurialism, anticommunism, market libertarianism, anticorruption discourse, and social conservatism); the common images and words capable of making these matrices compatible with each other (such as the concepts of ‘upstanding citizen’ and ‘mamata’, which are used to contrast those honest with those who supposedly threaten order and take advantage of public resources); the affective conditions that gave them resonance; and the organizational infrastructure on which they depend (such as churches, social media, and other communication networks).[11] I believe that in this answer I have addressed the economic libertarianism that underpins contemporary art; the moralism that, in varying degrees, brings together the various discursive matrices; and the malaise caused by the abuse of the vital force that characterize the affective conditions. Certainly, the most difficult answers still need to be worked on further.

2 An overflight in the southwestern region of Pará detected fires, deforestation, and illegal mining in conservation units. In this photo, a fire is seen in the municipality of Trairão. Photo by Marizilda Cruppe/Amazônia Real/September 17, 2020, in: Wikimedia

KR, FS: In light of the growing glorification of military dictatorships amid the rise of conservative and right-wing forces, and Bolsonaro’s rhetoric surrounding ‘culture wars’ and ‘Marxist culture’ as the ultimate threat, what similarities do you observe between the cultural policies of the Bolsonaro government and those of the military dictatorship?

LP: Bolsonaro served in the military for seventeen years and from 1988 built his political career by praising the dictatorship and denying the violations committed by the State – violations which began to be investigated with the establishment of the ‘Comissão Nacional da Verdade’ (National Truth Commission, 2011–2014) during Dilma Rousseff’s government. In 2016, when declaring his vote for Rousseff’s impeachment – who was arrested and tortured by the regime – Bolsonaro paid tribute to Colonel Ustra, a notorious torturer who died unpunished.

During his term as president, Bolsonaro appointed members of the military to high-ranking positions, but cultural sectors were somehow left out. I say “somehow” because agencies such as Funai (National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples) and Ibama (Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources) have been extremely militarized, facilitating, for example, extractive practices by agribusiness on indigenous lands and thus annihilating their ways of life and expressions. The images of fires associated with the advance of deforestation in the Amazon have become emblematic (fig. 2), especially in 2019, and they strongly mirror the occupation established by the dictatorship, whose legacy is still imprinted on the region. Accordingly, an ‘agro’ or “agrarian culture” has been strengthened: this is marked by masculine and heteronormative values, by the aesthetics of Nelore cattle and meat barbecues, and by sertanejo music (currently the most listened-to genre in Brazil). The land issue is fundamental here: if the 1964 coup was a response to prevent the possibility of agrarian reform, Bolsonaro certainly continued this offensive against land demarcation and distribution. From the dictatorship, Bolsonaro supporters also revived the specter of communism, linking it to the threat of “gender ideology,” which, in their view, is propagated by the predominance of leftist culture.

Something interesting I learned from authors such as Fabrícia Jordão is that, although the military dictatorship imposed censorship, persecution, and repression – which made leftist art and imagination unviable, driving many artists into exile – its cultural policy was defined by a hegemony of the left, due to the absence of a sufficiently articulated conservative aesthetic program. The regime’s intervention in the cultural sphere was associated both with the national development project – strengthening the market and the entertainment industry – and with the ideological foundations of the modernist project implemented during the Vargas dictatorship (1937–45), particularly the preservation of historical heritage. In 1974, the State approached the politicized artistic field with the creation of new cultural institutions and agencies, such as Funarte (National Arts Foundation), understanding that this field could be capitalized, and artists could be assimilated as professionals in the symbolic goods market. Jordão argues that, once incorporated into these State bodies, visual artists were able to engage in “institutional activism” to secure a space for the consolidation of contemporary art in Brazil – a form of production that, in order to be less dependent on the market, would require this alliance. But as we know, neoliberalism soon captured this line of flight as well.

3 Photograph of Bolsonaro in Armed Forces hospital on his Instagram account, 2021, Screenshot, Agenzianova, 14 July 2021, last accessed on 16 December 2025

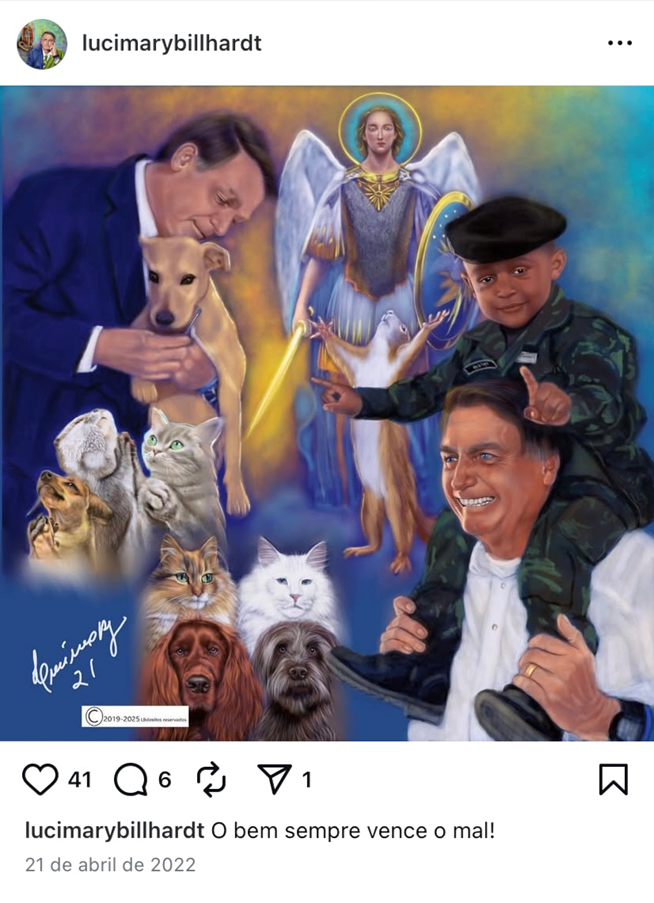

4 O bem sempre vence o mal! (Good always triumphs over evil!), painting by Lucimary Billhardt, 2022, promoted through her Instagram account, screenshot

KR, FS: Although the global New Right does not pursue a uniform cultural policy program, we have the impression that it does have comparable (albeit vague) objectives. Specifically, it believes, that art and culture should be more American, more French, more German, more Italian or more Brazilian or whatever. How would you describe the concept of culture under the Bolsonaro government? What significance did culture have for them? Who should create culture or the arts, and for whom?

LP: Nationalism certainly exists. The yellow jersey of the Brazilian national soccer team, known as ‘canarinho’ (canary), became one of the main visual markers of the far right, an association reinforced by the support of famous athletes, such as Neymar, for Bolsonaro. Soccer has always occupied a central place in Brazilian culture, but it is worth remembering that this pride was deeply shaken by the 7–1 defeat to Germany in the 2014 World Cup, played on Brazilian territory. Combined with the economic crisis that followed, it was a major collective trauma, and it became necessary to ‘honor the jersey,’ I risk to say. Other national symbols are mobilized by Bolsonarismo, such as the flag (and more frequently, the US flag), also reviving republican and monarchist symbols.

For Francisco Bosco, in addition to the cultural wars, the cultural dimension of Bolsonarismo is deeply rooted in Christianity. The association between religion and politics was decisive both for Bolsonaro’s election and, in another historical context, for the legitimization of the 1964 coup. The “March of the Family with God for Freedom,” mobilized against alleged communist infiltration that would threaten the country’s Christian values, served as an important tool of social and symbolic support for the military coup. But while the dictatorship sought to project a modernist and cosmopolitan aesthetic, Bolsonarismo bases its nationalism on a romanticism that rediscovers its sense of community in the “Christian soul” of European expansionism, as Bosco argues, especially through the discourse of then-Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ernesto Araújo, a staunch critic of Marxism.[12]

Christian conservatives constitute a majority segment among Brazilians, with the number of evangelicals growing steadily in recent decades and having an increasing influence on politics, as shown in the documentary Apocalypse in the Tropics (2024) by Petra Costa. This group voted overwhelmingly for Bolsonaro in both presidential elections. Unlike Catholicism, many evangelicals reject the worship of images – this is the case of former first lady Michelle Bolsonaro, who asked for the removal of all images of sacred art from the Alvorada Palace, including a painting by the famous modernist artist Djanira da Motta depicting orishas from the Yoruba religion (this had already been removed by the military man Ernesto Geisel, who was Lutheran). Evangelical Christianity culture is expressed mainly through gospel music, and some of its visual aesthetics have been documented by the duo of artists Bárbara Wagner e Benjamin de Burca in their film Holy Tremor (2017), as well as, in a more dystopian way, the feature film by Gabriel Mascaro, Divine Love (2019).

Bolsonaro also made religious appeals in the production of images for his government’s communications, which became known as the “Bolsonaro aesthetic”: an aesthetic that appeared improvised, sloppy, or clumsy, but which was the result of visual compositions carefully planned by a populist strategy. This is the case of a photo of the former president lying in a hospital bed (fig. 3), reminiscent of the famous painting Lamentation over the Dead Christ by the Italian Renaissance artist Andrea Mantegna. On social media, images were shared of Bolsonaro eating bread with condensed milk, recording speeches next to his clothesline at home, and using a surfboard to hold microphones at a press conference. By refusing the refined visual finish of political marketing, Bolsonaro consolidated his image as an anti-system politician. Curator Polyanna Quintella listed some occasions when Bolsonaro’s allies followed the same strategy, parodying these situations with performance art, such as the video of the Minister of Education Abraham Weintraub singing “it’s raining fake news!” while dancing with an umbrella.[13]

Finally, it is worth briefly mentioning the collection that Bolsonaro has built up during his term in office. Among the gifts he has received are paintings by Lucimary Billhardt, a supporter who made numerous colorful and caricatured portraits of him after noticing that there was a sparkle in his eyes that formed a cross. Billhardt, who frequently posts her paintings on Instagram (fig. 4), stated that her works could be part of the canon of “right-wing art,” and that her greatest inspirations are Michelangelo and Da Vinci.[14]Another work in the collection is a sculpture by artist Rodrigo Camacho in the shape of the map of Brazil made from bullet cartridges and bearing Bolsonaro’s face. This work uses a language that is not very different from what one can find in contemporary art galleries. As artist Pedro França said, Bolsonaro’s aesthetic echoes the modern avant-garde project of dissolving the hierarchies between works of art and everyday objects, but it dissolves the hierarchies between politicians and ordinary people. However, the heirs of this avant-garde react to this with “class prejudice,” like nobles indignant at the dubious taste and vulgarity of the right-wing, which does not recognize itself in Brazil’s supposedly ‘liberal and diverse’ culture, and which compares modernist designs to Disney sets.[15]Revising this reactive behavior is quite a challenge. I really like how Tamar Guimarães dramatized this problem in a humorous way in her SOAP series (2020), in which a group of left-wingers in Brazil and Germany attempt to infiltrate right-wing social networks by creating a telenovela.

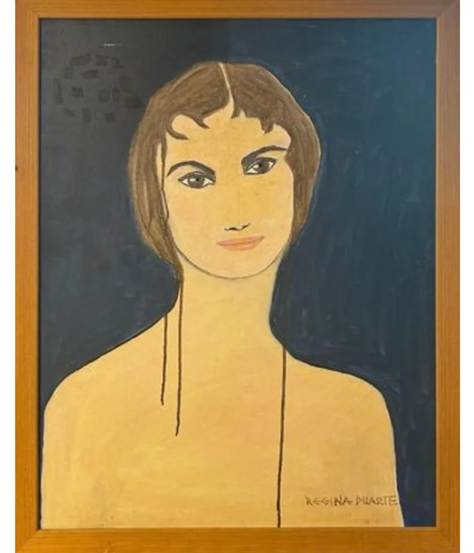

5 Regina Duarte: Franjinha (Fringe), 2001, oil/canvas, 84 x 68 cm, Reginadasartes

KR, FS: Are there key figures from the arts and culture sector who have acted as loyal supporters of the Bolsonaro government and thus as right-wing actors? Are there figures or institutions from this scene who can be said to have contributed to the creation of right-wing art and culture?

LP: There is a joke that the biggest political force in Brazil had become the “Tio do Zap,” which refers to that uncle or older relative that exists in most Brazilian families and who spreads far-right content, fake news, and conspiracy theories through the WhatsApp messaging app without thinking too much about the content. We can say this figure contributed a lot, in addition to the already mentioned sertanejo musicians and gospel singers linked to megachurches.

But since I talked about telenovelas, I also remember the actress Regina Duarte, a former soap-opera star who became Brazil’s culture secretary, replacing the secretary who had been dismissed after giving a speech that employed language reminiscent of Goebbels (and other two secretaries before him).Bolsonaro’s Secretary of Culture had a lot of turnovers: Regina Duarte was the fourth person to lead the office, yet she remained in the position for only a few months, leaving amid public backlash and pressure from the administration’s ideological wing.Away from television and politics, Duarte has been devoting more time to her work as a visual artist. She produces drawings, paintings, and collages using oil, colored pencils, chalk, and dried leaves (as shown on her official website, Regina das Artes, where she sells works at prices to suit all budgets).[16]Aesthetically, her works are close to amateur or decorative figurative art, marked by soft colors and simple compositions. The emphasis on nature, intimacy, and an essentialized notion of femininity like in her painting Franjinha (Fringe)(fig. 5) produces a docile and peaceful atmosphere, far from any explicit political or social tension. I keep thinking that this would be another type of visual art promoted by the right-wing if she were still in office.

Yet the most important figure was Olavo de Carvalho (1947–2022), a self-proclaimed philosopher, guru, and leading intellectual reference for the Brazilian far right. Since the 1990s – and even more strongly after the popularization of the internet in the 2000s – Olavo articulated an ideological system based on combating communism, defending “customs,” and denouncing the supposed cultural hegemony of the left. Living in Virginia, in the U.S., he accumulated thousands of followers on social media, where he spread conspiracy theories (often using foul language) and promoted an online course designed to combat the “cultural Marxism.” The anti-systemic character central to the rhetoric Bolsonarista would not exist without his influence, sustained by the affective mentorship he exercised over a conservative and strident youth, mobilized both by resentment and by the communicative effectiveness of the virtual sphere. His proximity to Steve Bannon further reinforced the convergence with the global far-right populism.

6 Pronouncement by Roberto Alvim in January 2020, in: Secretário da Cultura, Roberto Alvim cita ministro nazista em pronunciamento, 17 January 2020, in: Youtube, screenshot

KR, FS: In light of Roberto Alvim’s Goebbels quote, does Nazi ideology play any role in Bolsonaro’s cultural policy?

LP: Yes. I think this case is very important. Roberto Alvim was a well-known playwright in the theater world, mainly for the company he founded with his wife, Juliana Galdino, a renowned actress in the field. It is said that Alvim converted to conservatism and Christianity very suddenly and radically after receiving a serious health diagnosis. Alvim gained visibility from the far right after posting messages on social media supporting Bolsonaro and philosopher Olavo de Carvalho, speaking out that “[…] left-wing art is the indoctrination of all audiences; right-wing art is the poetic emancipation of each audience member.” [17] Bolsonaro stated that he had difficulty finding someone for the culture who would appeal to conservative and Christian voters. Alvim first held a management position at Funarte (the agency that allowed the artistic community to establish contemporary art in Brazil during the dictatorship). However, it was when he took over the Secretariat of Culture with carte blanche from Bolsonaro that he was able to push forward an ambitious project, in his words, “a cultural war machine,” to “generate a bombardment of conservative art on the population, a complete renewal of a new generation of conservative artists in Brazil.”[18] On the same day as his Goebbels-inspired statement (fig. 6), Alvim recorded a live video alongside Bolsonaro stating that the government does not censor, but rather engages in “curatorial selection.”[19] During the live broadcast, Bolsonaro enthusiastically responds to Alvim’s plan to call for films that address Brazil’s independence and great Brazilian historical figures. During the same live broadcast, Alvim briefly anticipated some of the intentions behind his program, which would be announced hours later under the Nazi aesthetic: “it will be the biggest cultural policy of this administration and one of the biggest cultural policies ever launched in the history of Brazil.” Finally, he stated that Brazilian culture – the foundation of the nation – is ailing, and that the “Prêmio Nacional das Artes” (National Arts Award) will signify the renaissance of art and culture in Brazil.

For it to become a scandal, the statement had to be dramatized using the acting skills Alvim had learned during his years in theater. Everything in the speech was very well thought out. Wagner’s soundtrack, Goebbels’ setting and quote: “The Brazilian art of the next decade will be heroic, and it will be national (…) or it will be nothing”.[20] Under public pressure, Alvim was dismissed, although he said that despite the unfortunate coincidence with the German Nazi regime, “the phrase itself is perfect.”[21] In his speech, I am also struck when he says that “the virtues of faith, loyalty, self-sacrifice, and the fight against evil will be elevated to the sacred realm of works of Art” (‘Art’ always with a capital letter).[22]

Rodrigo Nunes interpreted the Alvim case as a typical example of ‘trolling’ in contemporary alt-right culture, that is, a ‘joke’ that feeds on its own ability to test the limits in order to introduce controversial ideas into public debate. For Nunes, Alvim was fired for having misjudged the limits of trolling in his statement, producing an overly explicit discourse that made it possible to associate elements of Bolsonaro’s ideology with Nazism, even though he denied this association.

For anthropologist Adriana Dias, Bolsonaro’s base has always been neo-Nazi. Dias, who has spent decades researching neo-Nazi groups in Brazil, found documents showing this link since 2004, when Bolsonaro was a congressman. Although he has tried to erase this trail, partly because of his efforts to win evangelical Christian supporters through pro-Israel rhetoric, Bolsonaro has flirted with Nazism numerous times, such as when he took a photo with a Hitler lookalike.

KR, FS: What effect did this cultural policy have on the arts, artists, and exhibition institutions?

LP: During his short administration, Alvim made at least two very serious appointments: Sérgio Camargo to the Fundação Cultural Palmares, an entity dedicated to Afro-Brazilian culture, and Dante Mantovani to Funarte. Camargo is a right-wing black man who has said, among other things, that slavery was beneficial because black people have lived in better conditions in Brazil than in Africa. He was later removed from office after being accused of moral harassment and ideological persecution by employees. Mantovani came from the music industry and associated rock music with abortion and Satanism.

Support for the arts diminished significantly with the abolition of the Ministry of Culture, which was transformed into a ‘secretariat’ subordinate to the Ministry of Tourism and, as we have seen, its leadership has undergone rapid turnover, which has made it difficult to maintain continuity of long-term policies and planning, along with the period of lockdown to contain Covid-19 (even though Bolsonaro was against it). And, of course, the far right’s grand plan was to target the Lei Rouanet – for them a ‘mamata’, or in a rough translation, the “nursing teat”, from which left-wing artists would suckle endlessly. The sharp cut in public funding has greatly affected the arts, although many of the major visual art institutions are privately run and funded. This is the case of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (Masp), an institution where I worked as a curator until mid-2017. When asked how the Bolsonaro administration affected the museum, President Heitor Martins said that it was a difficult period and that the law is an absolutely essential mechanism for culture in Brazil in general, but that Masp has a diverse range of revenue streams and had the staying power to get through the period.[23] I bring up this example for two reasons: first, because since Martins took over, Masp’s artistic direction has been pretty progressive. Second, because Masp, due to its location on Avenida Paulista and its huge plaza/architecture, has become one of the main meeting points for political demonstrations in recent decades. During the years I worked there, I watched the rise of Bolsonarismo from the museum windows, and it always struck me how the leadership of the institution seemed immune, but also blind, to these movements around it.

The same does not apply to federal museums, and the fire at the Museu Nacional in September 2018 became a symbol of this process of institutional negligence and the fragility of cultural policies in Brazil, even though it preceded Bolsonaro’s presidency. In the context of scarce resources, the mobilization of the arts sector, in coordination with left-wing lawmakers, enabled the passage of the Aldir Blanc and Paulo Gustavo emergency laws, both named in honor of artists who fell victim to COVID-19.

KR, FS: Can you think of any exhibitions or festivals that particularly stood out because their program seemed to be shaped by the new cultural policy agenda?

LP: I can’t think of any examples like the ones I witnessed in Poland and the United States. What comes to mind are the military and patriotic parades celebrating Brazil’s independence on September 7, especially the bicentennial in 2022, with the loan of the embalmed heart of Brazil’s first emperor, Dom Pedro I. The event became a platform for Bolsonaro’s reelection campaign. I also remember the anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro mentioning that the Fundação Casa de Rui Barbosa in Rio de Janeiro, which had once hosted events that were crucial to Brazilian thought, such as the colloquium Mil Nomes de Gaia (A Thousand Names of Gaia, 2014), organized an exhibition and a series of events on Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. As far as I know, artist Marilia Furman has also been trying to conduct research in this direction.

7 Antonio Claudio Alves Ferreira was sentenced to 17 years in prison for breaking a historic clock during the invasion of the Planalto Palace in 2023, in: JJ – Homem que quebrou relógio histórico durante atos antidemocráticos é preso, 20 June 2025, Youtube, screenshot

KR, FS: Bolsonaro’s reign ended with an artistic bang, so to speak, as a significant part of his supporters’ storming of the Capitol involved the destruction of works of art. What was that all about? Would you say it was just collateral damage, or did the artworks have a meaning that needed to be smashed?

LP: We can interpret the invasion of the Congresso Nacional (National Congress), the Palácio do Planalto (Planalto Palace), and the Supremo Tribunal Federal (Federal Supreme Court) on January 8, 2023, in a similar way as the attack on the U.S. Capitol. Of these three buildings, the Federal Supreme Court was the most destroyed, as this body is the target of indignation and resentment among extremist Bolsonaro supporters, being perceived as an obstacle to their coup plots.

Once again, the easy answer is to say that the invaders vandalized everything in their path: furniture, computers, and artistic and historical artefacts were equally targeted by punches, piss, and feces, without judgment. This would mark a difference between today’s conservatives and those of the dictatorship era, who were concerned with preserving national heritage. Therefore, the irreparable destruction of a table clock from the days of the monarchy caused astonishment (fig. 7). Another damaged work often mentioned is the painting portraying women of mixed black and white ancestry made by renowned modern artist Di Calvalcanti. It was stabbed seven times. Bolsonaro’s supporters also attacked a hyperrealistic painting of the national flag. On the other hand, some say that a portrait of Bolsonaro, with which extremists took several selfies during the invasion, was stolen (taken as a souvenir?), as well as weapons.

The exact number of damaged works has not been officially disclosed, but it draws my attention how the press and the opposition used the monetary value of the affected pieces and the costs of their restoration to stir up public commotion. The invasion of Brasília represented a high point in the offensive ‘bolsonarista against culture’, however, I believe that some basic issues still need more consideration, such as explaining how one can learn more about the collections of the presidential palaces, how the collection was formed, and how it can be accessed.

It is worth remembering that Brasília was conceived to host the country’s political power, as part of a project of interiorization and national integration. Designed by Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer, it was inaugurated in 1960 as a landmark of modern world architecture. In recent decades, the city has had its tensions and contradictions explored by various theorists and artists. In 1959, art critic and activist Mario Pedrosa defined Brasília as the “synthesis of the arts,” a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk. The widespread attack on the buildings indicates the failure of this modern project.

8 In April 2025, Michelle Bolsonaro calls for new protests, holding a lipstick and asking for amnesty for the invaders of January 8, 2023, Assista ao discurso de Michelle Bolsonaro no ato de 6 de abril na Paulista, in: Youtube, screenshots

KR, FS: Is there a noticeable change in cultural policy following Bolsonaro’s defeat? Countries such as Poland, for example, are currently busy reversing the authoritarian structures that had been implemented. Is something similar happening in Brazil?

LP: The slogan of Lula’s government, replacing Bolsonaro in 2023, was “Union and reconstruction” (and in August 2025 it was recently replaced by “On the side of the Brazilian people”), seeking to handle the polarization of the country and restore institutions and public policies. This also applies to culture. The Ministry of Culture was reinstated, with singer Margareth Menezes appointed as its head, and through it, funds and the dialogue with the diversity of cultural practices. There is also a project for a Museum of Democracy underway, created in response to the attacks of January 8, 2023. Other important ministries were created, such as the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, under Sonia Guajajara, and the Ministry of Racial Equality, under Anielle Franco, sister of Marielle Franco, whose assassination in 2018 became one of the tragic milestones of the neoconservative rise in Brazil. But there are rumors that the current policy has focused heavily on the creative industry, favoring private management of cultural institutions and projects such as the Streaming Law that threatens Brazilian cinema.

Another major effort by the Lula administration has been to restore the country’s international reputation by hosting events such as the G20 and COP30 meetings. The climate agenda has been one of the priorities of his third term, but it is not free of contradictions, since he also authorized oil exploration at the mouth of the Amazon River and the construction work carried out to make COP possible impacted peripheral communities.

As I answer this interview, Bolsonaro has been arrested and sentenced to 27 years in prison for five crimes, including leading a coup plot. Hundreds of invaders of buildings in Brasília have also been arrested, and the military, once one of the pillars of the right-wing, has distanced themselves from it. With this, experts have indicated that although Bolsonaro is still relevant, Bolsonarismo is gaining autonomy and undergoing changes.[24] Anthropologist Isabela Kalil even speaks of an “aesthetic turn”: from a virile militaristic aesthetic to one of “bibles, lipstick, and flags” marked by martyrdom, religious faith, and femininity (fig. 8). The latter has been understood as resistance to the persecution of women arrested for damaging Brasília, with emphasis on the speeches of former first lady Michelle Bolsonaro.[25] The demand for “right-wing feminism” is a new trend that has been addressed by political scientist Camila Rocha.

Brazilian right-wing largely mirrors the United States. Trump’s operations to combat drug trafficking and immigration and his offensive against museums and universities may signal the policies that conservatives in Brazil may adopt. I believe that along with the work of looking more carefully at right-wing art, as you are proposing, the progressive side needs to create collective intelligence to deal more seriously with the severe problems we are facing, such as the climate crisis and the staggering power of big tech companies. In the post-pandemic era, the Brazilian art scene seems more diverse, internationalized, and professionalized, but institutions are still very fragile, and labor conditions are precarious. At the same time, there is a great fear that criticism could make this field even more vulnerable to future conservative attacks. That is why I also think it is worth reimagining the notion of criticism, one that is not based on accusation, but one that is capable of responding to differences.

[1] Félix Guattari, Suely Rolnik: Molecular Revolution in Brazil, Los Angeles, New York 2007.

[2] This context inspired the exhibition À sombra do futuro (Shadowed by the Future), curated by Deyson Gilbert, Roberto Winter and Luiza Proença at the Instituto Cervantes in São Paulo, 2010.

[3] See Nizan Guanaes: O termômetro da Bienal de São Paulo, in: Folha de São Paulo, 24 August 2010. The institutional changes at the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo were implemented by financial consultant Heitor Martins, who served as president of the foundation between 2009 and 2013. Since 2014, Martins has been president of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo.

[4] One example is José Olympio Pereira, an investment banker, former CEO of Credit Suisse in Brazil and President of the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo from 2018-2023. He is one of the largest art collectors in the world, focusing on modern and contemporary, See Filipe Lippe: It’s “Bolsonaro out” or nothing?. Arts of the Working Class, Oct 14 2021, https://artsoftheworkingclass.org/text/e-fora-bolsonaro-ou-nada, last accessed on 17 December 2025.

[5] Larne Abse Gogarty, Angela Dimitrakaki, Marina Vishmidt: Anti-fascist Art Theory. A Roundtable Discussion, in: Third Text 33, 2019, No. 3, pp. 449–465.

[6] Suely Rolnik: Spheres of Insurrection. Notes on Decolonizing the Unconscious. Translated by Sergio Delgado Moya. Cambridge: Polity, 2023.

[7] Déborah Danowski, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro: Is There Any World to Come?, in: E-flux 2015, No. 65, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/65/336486/is-there-any-world-to-come, last accessed on 15 December 2025.

[8] Fábio Cypriano: The São Paulo Biennial and the Paulista Elite, in: Charles Esche (ed.): The São Paulo Biennial and Its Discontents, 2018, in: https://www.saopaulobienalstories.org/, last accessed on 17 November 2025.

[9] Pablo Ortellado, Diogo de Moraes Silva (ed.): Políticas Culturais 15, 2022, No. 1: Dossiê Guerras Culturais, https://periodicos.ufba.br/index.php/pculturais/issue/view/2232, last accessed on 17 November 2025.

[10] Naomi Klein: The Shock Doctrine. The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, New York, 2007.

[11] Rodrigo Nunes: Of what is Bolsonaro the name?, in: Radical Philosophy 2020, No. 209, pp. 3–14, https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/of-what-is-bolsonaro-the-name, last accessed on 17 November 2025.

[12] Francisco Bosco: Face cultural do bolsonarismo explica destruição de obras de arte, in: Folha de São Paulo, 13 January 2023. https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/ilustrissima/2023/01/bolsonaristas-mijam-com-deus-sobre-a-cultura-brasileira.shtml, last accessed on 17 November 2025. I would like to thank Cayo Honorato and Diogo de Moraes for the reference.

[13] Pollyana Quintella: A estética de Bolsonaro. Governo institui nova categoria, a de político como Artista com A maiúsculo, in: Folha de São Paulo, 27 January 2020. https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/of-what-is-bolsonaro-the-name, last accessed on 17 November 2025.

[14] See https://tab.uol.com.br/stories/arte-de-direita/, last accessed on 17 November 2025.

[15] Pedro França: Intelectuais reagem com vício de classe à estética bolsonarista, in: Folha de São Paulo, 11 February 2020, https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/ilustrada/2020/02/intelectuais-reagem-com-vicio-de-classe-a-estetica-bolsonarista.shtml, last accessed on 17 November 2025.

[16] See her website: https://www.reginadasartes.com.br/, last accessed on17 November 2025.

[17] See Jan Niklas, Alessandro Giannini, Gustavo Maia. Roberto: Alvim convoca ‚artistas conservadores‘ para criar uma ‚máquina de guerra cultural‘, O Globo, 18 june 2019, in: https://oglobo.globo.com/cultura/roberto-alvim-convoca-artistas-conservadores-para-criar-uma-maquina-de-guerra-cultural-23747444, last accessed on 18 December 2025.

[18] See Secretário da Cultura, Roberto Alvim cita ministro nazista em pronunciamento, 17 January 2020, in: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3lycKFW6ZHQ, and Live da Semana – com Presidente Bolsonaro, Min. Abraham Weintraub e Sec. Roberto Alvim, 16 January 2020, in: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3lycKFW6ZHQ, and Live da Semana – com Presidente Bolsonaro, Min. Abraham Weintraub e Sec. Roberto Alvim, 16 January 2020, in:

[19] Live da semana, 2020.

[20] Alvim 2020.

[21] See Roberto Alvim ‚assina embaixo‘ frase de nazista, Jan 17, 2020, in: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AEeFlIr0d7I, last accessed on 17 December 2025.

[22] Alvim 2020.

[23] See Presidente do Masp cita dificuldades durante governo Bolsonaro: “Seis anos sem aprovar projeto”, 2 December 2024, in https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y65N4eLmPm4, last accessed on 17 December 2025.

[24] In a survey conducted by Genial/Quaest in November 2025, 13% of Brazilians said they were Bolsonaro supporters and 22% said they were right-wing but not Bolsonaro supporters. According to Felipe Nunes, author of the book “O Brasil no espelho” (Brazil in the Mirror), only 3% would form an “extreme right.”

[25] The lipstick has been used by Michelle Bolsonaro as a call for justice for Débora Rodrigues dos Santos, also known as ‘Débora do Batom’ (Débora with Lipstick), who was arrested after the attacks of January 8, 2023, in Brasília, when she wrote “You lost, dude” with lipstick on the statue “A Justiça” (The Justice), located in front of the Supreme Federal Court. In April 2025, Michelle Bolsonaro waved a lipstick at the crowd of a demonstration in São Paulo remembering Débora, and praised a banner among the crowd which was calling for amnesty for the “patriots” who had been confined to “concentration camps” after the invasion.